Thursday, October 27, 2011

Monday, October 10, 2011

Dr. Richard Koch dies at 89; medical pioneer

After the World War II bombardier became a doctor, he changed the way the developmentally disabled were treated and made huge strides in fighting PKU, a disorder that can cause mental disability.

In 1951, Koch — pronounced "coke" — earned a medical degree from the University of Rochester in New York, joined Children's Hospital Los Angeles and embarked on a groundbreaking career in developmental disabilities.

As a researcher, Koch devoted much of his career to preventing disability, specifically phenylketonuria, commonly called PKU, a hereditary metabolic disorder that can cause mental disability.

Early discovery allows for prevention, since the faulty gene that causes PKU enables the amino acid phenylalanine — contained in many foods — to build up in the blood and cause brain damage. PKU babies were placed on a tasteless no-protein diet and kept on it until they were about 10 years old, when their brains were sufficiently formed.

With Koch coordinating the effort, Children's Hospital served as the hub of a national drive to collect data on adult PKU patients and encourage those who were pregnant to return to the no-protein diet to increase their chances of having a healthy baby.

A memorial will be held at 4:30 p.m. Saturday at All Saints Church, 132 N. Euclid Ave., Pasadena.

LOS ANGELES – As a prisoner of war in Germany during World War II, Richard Koch chose his life’s work after reading one of the few books in the camp’s meager library – the medical biography “The Doctors Mayo.”

Liberated in 1945 after 13 months in captivity, he sped through his undergraduate years at the University of California, Berkeley, by persuading the school to give him course credit for his bombardier training in the Army Air Forces.

In 1951, Koch – pronounced “coke” – earned a medical degree from the University of Rochester in New York, joined Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and embarked on a groundbreaking career in developmental disabilities.

He pioneered mobile clinics that brought medical services to the disabled and led a landmark effort to screen newborns for a type of mental disability that can be treated with a no-protein diet, effectively putting an end to the disorder.

Koch, who had a heart condition, died Sept. 24 at his Los Angeles home, said his wife, Jean. He was 89.

He was an early advocate against institutionalizing the developmentally disabled, which was commonplace in 1955 when Koch was named director of the hospital’s newly established clinic for the study of mental disabilities.

The traveling clinics he created evolved into dedicated regional centers that enabled children to remain home with their families or live in a non-institutional setting.

“There was such a need, such a hunger. You can never forget that,” Koch said in the 2006 book “Over Here: How the G.I. Bill Transformed the American Dream.”

After California Gov. Pat Brown signed legislation in 1966 to create a regional-center system in California, Koch served as the founding director of a Children’s Hospital pilot facility now known as Frank D. Lanterman Regional Center. More than 20 eventually were established around the state.

As a researcher, Koch devoted much of his career to preventing disability, specifically phenylketonuria, commonly called PKU, a hereditary metabolic disorder that can cause mental disability.

He successfully lobbied for the first mandatory screening programs in the country, urging California and other state legislatures to require mandatory screening for PKU in newborns with a simple blood test.

Early discovery allows for prevention, since the faulty gene that causes PKU enables the amino acid phenylalanine – contained in many foods – to build up in the blood and cause brain damage. PKU babies were placed on a tasteless no-protein diet and kept on it until they were about 10 years old, when their brains were sufficiently formed.

By the late 1960s, the disease was largely under control. But around 1980, health officials noticed that female PKU patients saved from disability were giving birth to babies with mental disabilities and other disorders. PKU mothers who followed a regular diet were developing high blood levels of phenylalanine that damaged the fetus.

“Logically, we should have thought of it,” Koch told the Los Angeles Times in 1996. “But I think we were so enthused about these first PKU patients even being normal. That in itself was a shock.”

Unable to bear the thought that “a small army of patients that had been saved from this condition was producing a new flock of disabled children,” Koch secured a grant to deal with the problem, according to the book “Over Here.”

With Koch coordinating the effort, Children’s Hospital served as the hub of a national drive to collect data on adult PKU patients and encourage those who were pregnant to return to the no-protein diet to increase their chances of having a healthy baby.

Almost until the end of his life, Koch continued to treat PKU patients whom he first saw as infants decades ago, seeing them at his home near the hospital he retired from about five years ago.

“He was the most unassuming, gracious, gentle, kind-hearted man,” said Dr. Linda Randolph, head of medical genetics at Children’s Hospital. “You would never know how great he was and what a tremendous contribution he made in the fields of disabilities and PKU from a casual conversation. He never tried to impress anybody.”

He was born Nov. 24, 1921, in Dickinson, N.D., the sixth of nine children of Valentine Koch, a sheep farmer, and his wife, Barbara. His family moved to Petaluma when Richard was 7, and his father worked on a poultry farm.

At a USO dance, Koch met his future wife, who was playing marimba in the band. He headed off to war soon after they married in 1943.

In April 1944, Koch and his fellow Army Air Forces crew members were shot down while flying over Germany in a B-24 Liberator. He immediately was captured. While in the POW camp, he bartered for a typewriter and began a POW newspaper.

Once he was home, he bought an Army surplus Jeep for $150 that came in a crate, assembled it and drove it cross-country to medical school.

With his family, he often backpacked, once hiking 110 miles round-trip from Mineral King in Sequoia National Park to Mount Whitney and trekking 150 miles on the John Muir Trail.

He took a leave of absence in 1970 to spend a year in Peru with his family as a medical volunteer with Project Hope. Koch also taught medicine at the University of Southern California.

Well into his 70s, the dedicated environmentalist could be spotted riding his bicycle down Sunset Boulevard to work, his tie flapping in the wind.

In addition to his wife, Koch is survived by three daughters, Jill, Christine and Leslie, all of Los Angeles; two sons, Tom and Martin, both of Ridgecrest, Calif.; 10 grandchildren; and nine great-grandchildren.

1921-2011

Richard Koch was born in Dickinson, North Dakota in 1921, the 6th child in a family that eventually included seven boys and two girls. The family moved to Petaluma, California when he was a child and he attended elementary and high school there, graduating in 1941 and earning a scholarship at the University of California at Berkeley. In 1942 he enlisted in the Army Air Corps and was trained as a bombardier. He served in the 8th Air Force, based in England until his B-24 was shot down on April 9, 1944. He spent 13 months as a prisoner of war at Stalag Luft 1 in Germany. After the war, he finished his pre-medical studies and was accepted at the University of Rochester School of Medicine in New York, graduating in 1951. He interned at Childrens Hospital of Los Angeles where he eventually joined the staff and became a Professor of Pediatrics at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California. In 1957 he started a traveling clinic that brought a team of professionals to 13 southern California counties to serve children with developmental disabilities. In 1966 Governor Pat Brown signed legislation that used this model in establishing the Regional Center system in California. Eventually 21 Regional Centers were established throughout the state. Richard Koch became the first director of the Frank Lanterman Regional Center. In 1970 he took a sabbatical leave and he and his family spent a year in Peru where he was a volunteer for Project Hope. Over a span of more than 50 years, Richard Koch conducted extensive research on Down syndrome and rare metabolic disorders, such as PKU (Phenylketonuria). He was the principal investigator in the Collaborative Study of Treatment of Children with Phenylketonuria sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, which lasted 16 years. He was also the principal investigator of the International Maternal Phenylketonuria Collaborative Study. In 1962 he was actively involved in getting legislation passed in California mandating newborn screening for all babies born in this state. Since 1966 when the legislation passed, hundreds of babies have been diagnosed at birth and treated for severe genetic disorders. Dr. Koch was also involved in research to establish guidelines for getting FDA approval for biopterin for the treatment of PKU in the U.S. This product is now available under the trade name Kuvan and is the newest treatment for many people with PKU. He also pioneered in the treatment of persons with PKU who are disabled because they were born before newborn screening. In 2004, a new group home specifically for late-treated persons with PKU was named in his honor – The Koch-Vagthol's Metabolic Residential Care Center in Burbank, California. Dr. Koch has had more than 200 articles published in peer-reviewed professional journals. He married Jean Holt in 1943 and they raised five children. The family spent many summer vacations back-packing in the Sierra, including a 110 mile round trip hike from Mineral King to Mt. Whitney and a 150 mile hike on the John Muir Trail. He and Jean were active in efforts to save Mineral King from commercialization in the 1970s. This battle was won and Mineral King is now part of Sequoia National Park. Richard Koch is survived by his wife, Jean, his daughters, Jill Koch Tovey, Christine Koch Wakeem and Leslie Koch and by his sons, Tom and Martin. He also leaves ten grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren. He passed away peacefully in his home on September 24, 2011. He lived a full, adventurous life and accomplished much. A memorial service and reception will be held at All Saints Church, 132 N. Euclid Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91101 on Saturday, Oct. 8 at 4:30 P.M. Donations in his memory can be made to Mt. Hollywood Congregational Church, 4607 Prospect Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90027 or to the Guthrie-Koch Scholarship Fund at 6869 Woodlawn Ave. NE # 116, Seattle, WA 98115-5469.

http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/latimes/obituary.aspx?n=richard-koch&pid=153877613

http://www.pkuheroes.org/drkoch/

http://www.npkua.org/

Labels:

California,

Dr. Richard,

Koch,

medical,

Obituary,

pioneer PKU

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

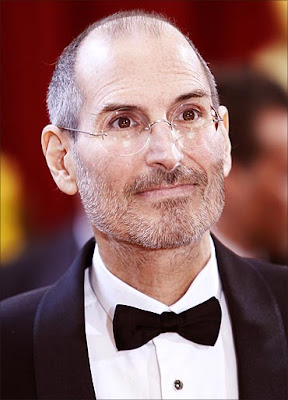

Steve Jobs dead October-05-2011

father Abdulfattah Jandalai

What most fail to realize is that his living biological father is of Syrian origin. Abdul Fattah “John” Jandali emigrated to the United States in the early 1950s to pursue his university studies. Most media outlets have published little about Jandali, other than to say he was an outstanding professor of political science, that he married his girlfriend (Steve’s mother) and by whom he also had a daughter, and that he slipped from view following his separation from his wife.

Later in life, Jobs discovered the identities of his birth parents. His mother, Joanne Simpson, was a graduate student at the time and later a speech pathologist; his father, Abdulfattah John Jandali, was a Syrian Muslim who left the country at age 18 and reportedly now serves as the vice president of a Reno, Nevada casino. While Jobs reconnected with his mother in later years, he and his father remained estranged.

Jandali in Syria

Abdul Fattah Jandali was born in 1931 to a traditional family in Homs, Syria. His father did not reach university, but was a self-made millionaire who owned “several entire villages”, according to his son. His father held complete authority over his children, authority not shared by his traditional and “obedient” wife.

“My father was a self-made millionaire who owned extensive areas of land which included entire villages,” Jandali said. “He had a strong personality and, in contrast to other parents in our country, my father did not reveal his feelings towards us, but I knew that he loved me because he loved his children and wanted them to get the best university education possible to live a life of better opportunities than he had, because he didn’t have an education. My mother was a traditional Muslim woman who took care of the house and me and my four sisters, but she was conservative, obedient, and a housewife. She didn’t have as important a part in our upbringing and education as my father. Women from my generation had a secondary role in the family structure, and the male was in control.”

Steven Paul Jobs was literally a child of Silicon Valley. Born out of wedlock in San Francisco, his birth mother, Joanne Simpson, was a graduate student he tracked down as an adult with the aid of a private detective. Jobs never publicly discussed his biological father, Abdulfattah "John" Jandali, a native of Syria. Simpson put the baby up for adoption, with the understanding that he be placed with a well educated family. Simpson initially balked when his adoptive family turned out to be high-school dropout Paul Jobs and his wife, Clara, who never finished college.

Jobs said his birth mother signed the papers only when his adoptive parents promised to send him to college. But he considered it lucky that his dad, a machinist, moved the family to Mountain View when Jobs was a boy and gave him a workbench in their garage.

Jandali and Joanne Simpson are the biological parents of Steve Jobs, who was given up for adoption because Simpson's father was against her marrying a Syrian man.

Jobs was born in San Francisco and was adopted by Paul and Clara Jobs (née Hagopian)[unreliable source?] of Mountain View, California, who named him Steven Paul. Paul and Clara later adopted a daughter, whom they named Patti. Jobs' biological parents – Abdulfattah John Jandali, a Syrian Muslim graduate student from Homs who later became a political science professor, and Joanne Simpson (née Schieble), an American graduate student who went on to become a speech language pathologist– eventually married.

"No one wants to die," Jobs said in his 2005 speech at Stanford. "Even people who want to go to heaven don't want to die to get there. And yet death is the destination we all share."

RENO - Somehow it has escaped almost everyone's notice for decades that the father of the man who transformed Apple Inc. from a tech has-been to one of the world's most valuable companies has been quietly living in Nevada.

The resignation of Steve Jobs last week prompted a round of media retrospectives on his storied career. It also snatched his biological father - a longtime Reno restaurateur, casino executive and former political science professor and one-time Las Vegas resident - from relative obscurity.

In the days following Jobs' announcement, Abdulfattah John Jandali, 80, broke his decades-long practice of avoiding media interviews to speak with a British tabloid about his wish to meet the famous son he gave up for adoption in 1955.

Although many who worked closely with Jandali at Boomtown Hotel knew he had fathered Jobs, the relationship was not widely known beyond the casino or often discussed openly.

Many in Reno's political and business elite never knew that the man who produced one of America's best-known business geniuses lived in their midst. The local newspaper never reported on Jandali's famous progeny.

"Jeez, you leave the office for 10 minutes to get a sandwich and look what happens," said state Sen. Ben Kieckhefer, R-Reno, who learned of the relationship when a reporter called him Monday.

Reno Mayor Bob Cashell, who transformed Boomtown from a mom-and-pop truck stop into a resort in the late 1960s, also was unaware.

"Really?" Cashell said when a reporter told him of the relationship.

¶"I've met the man once. I had no idea."

Apparently, only those closest to Jandali were aware he is Jobs' biological father.

"I did know that, but it's kind of a secret," said Dick Scott, a longtime Reno gaming executive, who was general manager of Boomtown before Jandali started work there.

"He doesn't talk about it a lot, only to people he's really close to."

Scott, whose son-in-law Jack Fisher took over as general manager of Boomtown and worked closely with Jandali, told Scott of the relationship.

"I remember Jack Fisher walked in one day and told me that," Scott said. "I said, ÔYou gotta be kidding me.' He said, ÔNo. True story.'"

Fisher confirmed that Jandali doesn't speak openly of his son.

"It's a personal thing with him," Fisher said. "I happened to come across it and asked him about it, and we haven't really talked about it since."

Jandali did not return repeated phone calls from the Las Vegas Sun. A spokeswoman for Pinnacle Entertainment, which owns Boomtown, said it would be inappropriate to comment on the relationship.

But the spokeswoman noted that it's fairly well known at the company.

"I'm pretty sure most people have known for a while," she said. "I was surprised people were surprised."

Jandali, who was born in Syria and educated in Beirut, has lived in Reno for decades, including working as a political science professor at UNR in the late 1960s.

His former colleagues in academia knew nothing of his son.

"Is this a crank call?" joked Eric Herzik, a political science professor at UNR since the late 1980s. "I've never heard that story."

Joe Crowley, former UNR president who was a political science faculty member with Jandali, knew nothing of the relationship. He described Jandali as a "very bright guy."

"If that story is true, it wouldn't be surprising that Steve Jobs is his son because John is very smart," Crowley said.

Don Driggs, who was chairman of the political science department when Jandali taught at UNR and now lives in Chandler, Ariz., described Jandali as having been a "brilliant young man."

"That's amazing," Driggs said. "That's really something. He's the biological father of one of the most famous men in the world?"

Fisher described Jandali as a "very kind man" and a "health nut" who exercises daily and is scrupulous about his diet.

"He's one of the sharpest men I've ever known," Fisher said. "He's very creative. He's very flexible when it comes to managing. I've always admired him for that."

When it became known that Jobs was ill with a rare form of pancreatic cancer, Jandali mailed him his complete medical history with the hope it might help his ailing son, Fisher said.

Jandali's time in Nevada is somewhat unclear. In addition to teaching at UNR in the late '60s, he has managed several Reno restaurants and worked in Las Vegas for a time. According to his LinkedIn profile, he began work at Boomtown as the food and beverage manager in 1999. He was promoted to general manager last year.

Jandali's story hasn't been widely told. According to several national news accounts, Jobs has never spoken publicly of his biological father.

The British tabloid reported that while Jandali longs to connect with Jobs, his "Syrian pride" has stood in the way.

"This might sound strange, though, but I am not prepared, even if either of us was on our deathbed, to pick up the phone to call him," Jandali told the newspaper. "Steve will have to do that as the Syrian pride in me does not want him ever to think I am after his fortune. I am not. I have my own money. What I don't have is my son ... and that saddens me."

Jobs' biological mother, Joanne Schieble, and Jandali weren't married when she became pregnant. They gave him up for adoption in San Francisco.

The couple later married and had a daughter. They divorced when she was 4 years old. Mona Simpson is now a noted author and has reportedly reconnected with her father.

The story of Jandali has captured the attention of some scholars involved in the nature versus nurture debate following the success of his two biological children - neither of whom he had a hand in raising.

Born Steven Paul Jobs

February 24, 1955(1955-02-24)

San Francisco, California, U.S.

Died October 5, 2011(2011-10-05) (aged 56)

Palo Alto, California, U.S.

Cause of death Respiratory arrest/pancreatic cancer

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2011/10/05/BUU013D45T.DTL#ixzz1ZxVJqn7K

video

http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/steve-jobs-biological-father-regrets-adoption-report/story?id=14381769

http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/steve-jobs-biological-father-regrets-adoption-report/story?id=14381769

http://gma.yahoo.com/steve-jobs-dies-apple-chief-created-personal-computer-231337236.html

http://www.yahoo.com/

Sunday, October 2, 2011

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)